Welcome to part 2 from my examination of the lack of racial diversity in fashion media (for part 1, click here). This time I'll be looking at the horrendous use of 'Blackface' in editorial, which is a problem that many editors refuse to acknowledge. Personally I find it upsetting that this kind of insensitivity is continuing in the 21st century and it made me determined to expose these incidents.

*

If you pick up any

fashion magazine, it is more than likely that there will be a dearth of white

models and public figures within its pages but only a handful of examples from

other races. There are many successful non-white celebrities and models that

could easily grace the covers of a fashion magazine, but are simply not given

the opportunity. For the magazine editors and advertisers, this is simply

justified by the knowledge that a black cover star results in lower sales

figures, meaning that the magazine makes less profit, so it is logical from a

business angle to continue to use white cover stars. The financial burden of

running a magazine means that advertisers are necessary to provide crucial

support; without the endorsement of those advertisers, the magazines would not

be able to make a profit. Therefore black models will continue to merely make

rare cover appearances in order to placate the ethnic minority audience and

keep up appearances of political correctness. With this in mind, I would like

to examine several controversial photo shoots employing white models made to

adopt the image of their black counterparts, and look at the possible reasons

behind these being published as fashion.

[Taken from Vogue Paris].

The

first of these images is Lara Stone, photographed by Steven Klein for Parisian

Vogue. The photo shoot showed Stone in a variety of guises, sometimes coated in

dark paint and sometimes in cracked white paint which bore the appearance of

emulsion. However, the main difference between these two is that the white

paint was obviously not true to any skin colour, but the ‘blacked up’

photographs made any viewer unfamiliar with Stone believe that she was

non-Caucasian. Furthermore, she was dressed in a fur headpiece and gloves which

were reminiscent of stereotypically ‘ethnic’ clothing and, though carrying a

cane, this could easily have been mistaken for a spear as its tip is out of

shot. This gave the impression that the shoot was mimicking the tribal roots of

Africa, but not in a flattering light. If Stone had been painted in heavy

black, crackled layers, as in the white paint images, the criticism might not

have been so harsh but, as the photograph on the left proves, she was made to

imitate a person of African descent. Claire Sulmers, journalist and editor in

chief of the website The Fashion Bomb, wrote that ‘Though Lara Stone is

missing the white outline around the mouth or bright red lipstick [used in

‘blackface’], this photo shoot definitely strikes a raw nerve’. She goes on to

add that ‘Ms. Stone is the only “woman of colour” who scored a multipage

editorial’, which makes the photo shoot more offensive because it highlights

Parisian Vogue’s inability to take non-Caucasian models seriously in editorial

content. Sulmers has worked for Parisian Vogue’s website in the past, making

her viewpoint even more important, as she would have struggled to criticise an

institution she had been employed by unless she felt it essential.

[Taken from V Magazine].

The

second image is taken from Visionnaire, or V, Magazine, and features Sasha Pivovarova

in full body make-up, embracing an unpainted model in a monochrome photograph. Both

girls are naked and are accompanied by the caption ‘Black is the new black’,

which is a quote taken from James Kaliardos, the Creative Director of L’Oreal,

when discussing beauty trends for 2010. As writer Laura Kenney asked, ‘Why

didn't the magazine use a darker-skinned model instead of painting a white

model black?’, and she also noted that V Magazine proclaimed "2010 sounds

like the future, and this is what it will look like," (2009). The shoot is

obviously designed to be artistic and visually arresting for the viewer, but

does that mean the future of beauty is to appear black but to outlaw black models?

It is hard to believe that many readers would find ‘blacking up’ to be creative

or challenging; instead it's merely outdated and embarrassing to look at.

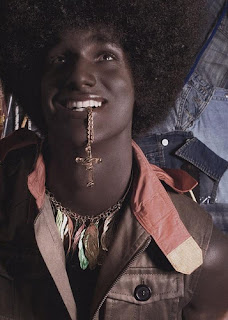

[Taken from L'Officiel Hommes magazine].

The

third example of ‘blackface’ in editorial content is unusual because it

involves a man, rather than a woman, being made to appear non-Caucasian. This

is the first publicised instance of male ‘blackface’ in a fashion publication

and it is probably the most shocking of the three images I’m analysing, mainly

because of the high quantity of photographs and also the unambiguous nature of

the resulting shoot. Milan Vukmirovic directed Arthur Sales for L’Officiel

Hommes magazine’s feature, Keep It Goin’

Louder, in which Sales was painted to resemble an African-American,

complete with a large afro wig and glowing white teeth. The feature was

designed to explore the return of Americana influences in men’s fashion, but

Sales’ appearance completely dominates the entire shoot.There is no logical reason to have chosen Arthur Sales over a photogenic African-American model. The addition of the afro wig also seems to be even more culturally insensitive.

What’s wrong with ‘Blackface’?

In order to understand

why the black community is offended by ‘blackface’, we must first examine its

place in history as a comedic tool used on stage. Performers ‘blacked up’ to

demonstrate the stereotypical character of the downtrodden black man, who bore

clown-like make-up and had exaggerated facial expressions, thereby

‘caricaturing black people and depicting them as being both stupid and

credulous’ (Malik, S., 2010). The Black and White Minstrel Show could be seen

on prime-time British television until 1978, giving millions of people a very

narrow-minded view of the ‘other’ in society. In the fashion world, some models

with non-white ethnicity were able to build a successful career, but these

women were exceptions to the unwritten rule that white women should dominate

fashion magazines. Today’s society has welcomed black celebrities and models,

but not as readily as the public are led to believe, and that is why modern

‘blackface’ scandals are particularly shocking. It is offensive enough to see

any race being ridiculed, but to use a white model in make-up instead of a

black model is completely unnecessary on a practical level in today's society.

All major modelling agencies harbour a small but diverse range of non-white

models and it is not acceptable to say that a non-white model is not readily

available or professional enough.

*

Stay tuned for part 3, where I'll be asking what academics and industry insiders have to say about racial diversity.